Uber. Amazon. AirBnB. WeWork. Common.

These are some of the prominent brands and business platforms that have come to define the “shared” or “gig” economy in the U.S. and beyond. They are reflections of and responses to societal and behavioral changes in the ways that people want to live, work, and play. Their success is linked inextricably to the ubiquity of mobile tools that connect users to the Internet that, as one AEC firm put it, “is the circulation system of the shared economy.”

As this economy evolves and expands, the built environment plays catch-up. Indeed, some AEC executives still view this evolution through a narrow framing of “collaborative spaces” and transparency. These same executives, though, acknowledge that something is going on out there that is redrawing design and construction parameters.

These influences vary by building type and manifest themselves in different ways. For example, Thousand Oaks High School in California recently completed the transformation of its 4,500-sf library into a Perkins Eastman–designed Learning Center that “is like Starbucks without coffee,” say two of the firm’s Principals, Brian Dougherty, FAIA, LEED AP; and Betsy Olenick Dougherty. The Learning Center is “energized” with nonstop music and strong bandwidth. The space’s lighting, acoustics, and tools (it includes 3D printers) are completely different from a traditional library’s, and the librarian now serves as a facilitator and mentor.

In Lowell, Mass., Maugel Architects designed the 100,000-sf Boott Mills office building (which includes labs on its third floor) with large, flexible conference spaces that all tenants can share.

On a grander scale, Sidewalk Labs, an Alphabet-owned company, is developing a 12-acre neighborhood, called Quayside, southeast of Toronto, whose objectives include creating a destination for people, companies, startups, and local organizations “to advance solutions to the challenges facing cities, such as energy use, housing affordability, and transportation,” according to the project’s website.

“I think [the shared economy] is having a bigger impact than most people realize,” says Rhett Crocker, President of LandDesign, a Charlotte, N.C.-based urban design, planning, and civil engineering firm.

Before Crocker spoke with BD+C in mid-March, he had a conversation with a client about developing pickup and drop-off areas for car-sharing services and the city’s popular bike- and scooter-sharing programs. (Since the city launched its electric scooter program in May 2018, monthly ridership has ranged from 83,000 to 139,000 trips, according to the Charlotte Department of Transportation.) Crocker notes that some existing drop-offs have become little social hubs in their own right.

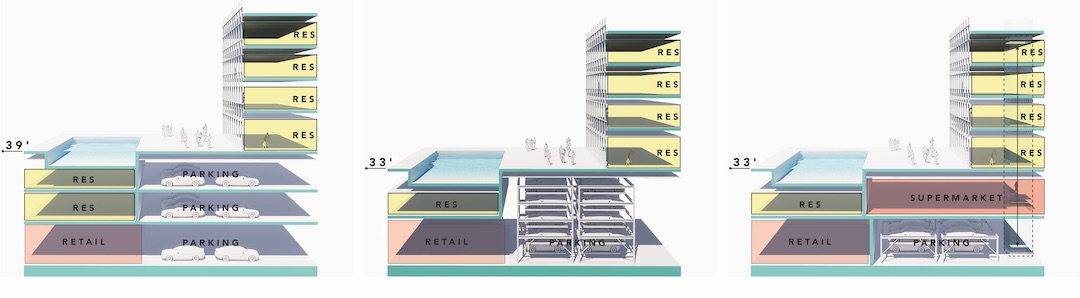

CBT Architects conducted a parking study for a Boston-area mixed-use development. The diagram below compares conventional parking with a parking-stacker model that includes one example where the model is flexible enough to be reprogrammed. At 10 Farnsworth, a nine-unit residential building incorporates a two-level semi-automated parking stacker system (at grade) to leverage that space for other potential uses such as retail. Courtesy Chuck Choi.

CBT Architects conducted a parking study for a Boston-area mixed-use development. The diagram below compares conventional parking with a parking-stacker model that includes one example where the model is flexible enough to be reprogrammed. At 10 Farnsworth, a nine-unit residential building incorporates a two-level semi-automated parking stacker system (at grade) to leverage that space for other potential uses such as retail. Courtesy Chuck Choi.

Ben Wrigley, AIA, Principal with Solomon Cordwell Buenz (SCB) in San Francisco, has also seen more scooter traffic buzzing around his city. “With no marketing, no instruction, younger people just seemed to know what to do.”

That spontaneity and unpredictability about where the shared economy is headed next have left AEC firms and their clients scratching their heads over formulating strategies. “Not only are these activities hard to control, but the people who are successful at this pride themselves as guerrilla businesses and great disruptors,” says Wrigley.

The following looks at how the shared economy is affecting design and construction of nonresidential and multifamily buildings. For some types, it’s still just conjecture; for others, the shared economy is fundamentally altering the game.

“It’s not so much about changing the physical infrastructure as it is about changing the operational structure,” says Kishore Varanasi, AISP, Principal, Director of Urban Design with CBT Architects.

1. Lobbies lay out the welcome mat

Lobbies are where people form their first impressions of buildings. But lobbies have also tended to isolate tenants and guests from the general public and community. The advent of the shared economy is changing that.

CBT does a lot of multifamily and office design, and Varanasi has noticed that lobbies in newer buildings are more adaptable to include popup retail installations for temporary tenants.

“Lobbies are now designed to welcome everyone,” says Sharon Bilbeisi, AIA, Associate Principal with Forrest Perkins. This is evident in hotel lobbies that are closely aligned with their venue’s food and beverage program. Forrest Perkins recently repositioned the lobby at the Fairmont Hotel in Washington, D.C., by moving the bar “front and center,” and creating “gathering zones” with varying sizes and privacy levels, says Bilbeisi.

2. Managing the package deluge

Lobbies sometimes double as repositories for delivered packages. But with online shopping accounting for 14% of total retail sales last year, the sheer volume of deliveries is overwhelming them. Consequently, designs for new buildings often include larger areas for package receipt and storage.

Mark Pelletier, AIA, Principal with Maugel Architects, says his firm is designing three apartment buildings that take into consideration more space for deliveries. His firm has looked at a number of package management systems, including Package Valet, and estimates that such systems require a 10×12-foot room for every eight apartments.

John Cetra, Founding Principal with CetraRuddy Architects, is also seeing more space being allocated for packages. In places like New York, where curbside parking is limited, his firm’s designs “try to make it easier for couriers to get in and out of buildings.” But such access must also be coupled, for security reasons, with service staff or an automated way to receive packages when tenants aren’t present.

The co-working firm Spaces is among the first tenants at Deep Ellum, an entertainment district in Dallas that Asana Partners is redeveloping to bring a variety of uses to a growing residential population by tapping into the urban industrial character of the site with a fresh design. Courtesy LandDesign.

The co-working firm Spaces is among the first tenants at Deep Ellum, an entertainment district in Dallas that Asana Partners is redeveloping to bring a variety of uses to a growing residential population by tapping into the urban industrial character of the site with a fresh design. Courtesy LandDesign.

3. Car sharing and ‘futureproofing’ parking structures

Cetra has noticed more couriers and residents getting around town on bikes. He’s also noticed some street parking in Brooklyn is reserved for car-sharing services.

There’s no question that the automobile has lost some of its cachet as a symbol of individual mobility. New vehicle sales actually rose slightly in the U.S. last year. But some 48 million Americans also used Uber’s services—which now include food delivery and business transportation—at least once in 2018.

Even though Uber and Lyft continue to lose money, demand for their services raises questions about the future of car ownership and parking requirements. “We are asking clients, ‘How are you developing for how people view cars in their lives?’” says SCB’s Wrigley. He notes that cities like San Francisco “have moved from minimum parking requirements to maximum parking requirements.” And while some developers still need convincing about reducing parking for their buildings, “they also realize they may have too much, and that expense, if saved, could be used for something else in the building.”

SCB is working on a project in Oakland, Calif., where the owner had developed a residential high-rise with 400 units, five stories over parking. The developer concluded that it couldn’t afford that building, and SCB came up with an alternative that, says Wrigley, required only about one-fifth of the garage space by relying on mechanized parking for storage.

Developers and their AEC partners are investigating how parking garages can become something else if the need for parking diminishes. CBT Architects recently conducted a study for a Boston-based mixed-use development, which showed how a conventional parking garage could save space by using mechanized stackers that, if parking needs changed, could be removed and replaced with

different programming, such as retailing or amenities for the building (see diagram, page 39).

One such example of future-proofing parking garages can be found at 10 Farnsworth, a new, nine-unit residential building in Boston’s Fort Point neighborhood, which incorporates an at-grade two-level semiautomated parking stacker system that can fit 10 cars within a fraction of a normal footprint. This solution allows the building owner to leverage the parking space for other potential future uses, like ground-floor retail or even more apartments.

Varanasi cautions, however, that variables which could affect parking in the future—most specifically, autonomous vehicles—“are changing every day.” That unpredictability had to be factored into CBT’s master plan for Cambridge Crossing, a 43-acre, 20-block transit-oriented neighborhood in East Cambridge, Mass., with 4.5 million sf of planned commercial, retail, and residential space.

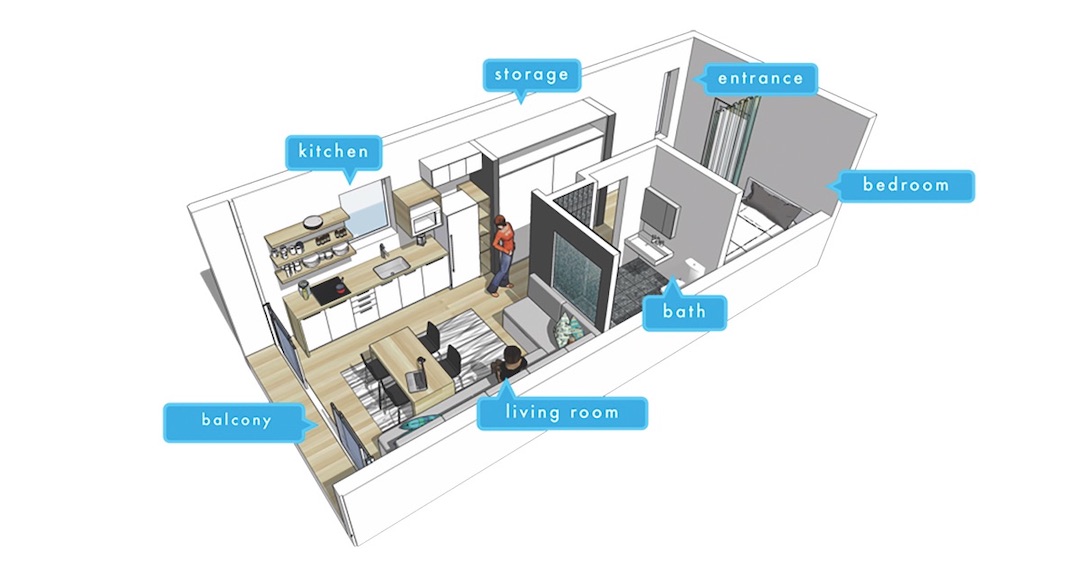

Stantec recently worked with the city of Boston to develop an “urban housing unit” as part of the city’s testing of different size apartment guidelines. The unit, around 400 sf, could possibly be a model for a pod that’s part of a co-living apartment. Stantec showed this unit to more than 2,000 people in six neighborhoods. Courtesy Stantec.

Stantec recently worked with the city of Boston to develop an “urban housing unit” as part of the city’s testing of different size apartment guidelines. The unit, around 400 sf, could possibly be a model for a pod that’s part of a co-living apartment. Stantec showed this unit to more than 2,000 people in six neighborhoods. Courtesy Stantec.

4. Co-working catches on

Last year, Pelletier of Maugel Architects hired an intern. After a week anchored to a desk, the intern asked, “Do I have to sit here?” The next day, he came into the office with a beanbag and laptop. “He did a ton of work for us after that,” says Pelletier.

The point of this anecdote is that there’s no telling how people want to work, which is why office design places a premium on creating flexible spaces that let employees find their own comfort zones.

This new work ethic has spurred the rise in co-working spaces, led by WeWork, which in eight years has grown from one location in SoHo, N.Y., to becoming the single-largest private occupier of space in London, Washington, D.C., and Manhattan. At the end of 2018, WeWork had 400,000 members working at 400 locations in 99 cities in 26 countries. The company has expanded its portfolio to include event planning and management, startup incubation, and education.

Demand has spawned a host of other co-working companies—with names like Impact Hub, Your Alley, Knotel, and District Cowork—vying for the growing number of businesses and employees seeking this kind of workplace alternative.

Inside the urban housing unit. Courtesy Stantec.

Inside the urban housing unit. Courtesy Stantec.

Most co-working locations are adaptive reuses of existing buildings. But there are some examples of new construction that are specifically for co-work leasing. One of these is 433 Broadway in Manhattan’s SoHo district, a six-story building that owner Omani Properties opened a few years ago. The building’s 100×125-foot floorplates accommodate workstations that range from 90 to 350 sf. Each of the working floors has its own courtyard. Cubico, a creative shared workspace, is the building’s primary tenant among the 120 companies leasing space.

RTK+B designed this building, and two of its architects, Peter Bafitis and Carmi Bee, explain that ground-up construction allowed for greater flexibility when it came to running systems through the building, and positioning interior columns to optimize floor space for different-size rentable workspaces.

5. Co-living populates both coasts

For those who view co-living as a commune-hippie-student-hostel-European concept, you might want to rethink your perceptions. The number of people willing to share living quarters with strangers is expanding in several of America’s largest cities.

Last October, a leading co-living brand, Starcity, announced plans to open more than 1,000 units in San Francisco and San Jose. Another expanding brand, Common, in March entered into a strategic alliance with Proper Development on a $100 million plan to build seven buildings with 600 beds in Los Angeles over the next two to three years. That same month, WeWork’s WeLive division hired a former Google exec to launch a “future cities project,” to address problems caused by globalization, urbanization, and climate change. The company’s Co-founder Adam Neumann says WeLive “wants to build a world where no one is alone.”

The East Coast is being infiltrated by co-living companies such as U.K.-based The Collective, which plans to open its first U.S. location in either Brooklyn or Queens, N.Y., and is also looking for locations in Boston and Chicago. The Collective’s U.S. expansion will follow its “Old Oak” model in London, which favors smaller (150- to 250-sf) units with large communal spaces on each floor. Germany-based Medici Living Group, which markets its co-living buildings under the Quarters brand, has units in New York and Chicago, and intends to spend $300 million over the next three years to add 1,300 rooms in U.S. cities with large pools of tech workers.

Floor plan of the urban housing unit. Courtesy Stantec.

Floor plan of the urban housing unit. Courtesy Stantec.

Co-living “is a word that’s used at the start of every conversation” he has with multifamily clients, says SCB’s Wrigley. Despite the “huge service management costs associated with it,” demand for co-living is changing what’s acceptable in residential high rises. “I’m seeing apartments I’ve never seen before: four bedrooms, two baths in downtown urban markets. It’s like an intersection of a dorm room and apartment,” says Wrigley.

One of the roadblocks to building co-living apartments has been zoning that requires minimal unit sizes. The City of Boston, under its Compact Urban Living pilot, has been testing different apartment-size guidelines, which Stantec helped the Mayor’s office design, according to Aeron Hodges, a Stantec Associate.

Stantec’s Chicago office worked with Medici Living on its 14-unit co-living building in Chicago’s Fulton Market neighborhood. And to help Boston gather input from local residents about the acceptability of smaller apartments and communal living, Stantec built a 385-sf, one-bedroom mockup on wheels that it showed to more than 2,000 people in six neighborhoods. Hodges says the feedback about this unit found people willing to share certain things—workspaces, kitchens, bike storage, appliances—but less willing to share others, like bathrooms.

Hodges notes that most co-living brands have yet to crack the affordability code. And she thinks this lifestyle model will be harder to pull off in less-dense markets. But Hodges also suggests that co-living could be attractive in markets near urban cores that don’t already have social hubs.

6. ‘Authentic’ is the new refrain

Since it launched in 2008, Airbnb, the online marketplace and hospitality service, has turned the hotel industry upside down. The San Francisco-based company currently has more than six million listings in 81,000 cities and 191 countries. Many of these listings are private homes whose owners lease space to travelers. Over the past decade, more than 400 million guests have booked accommodations through Airbnb.

“Airbnb has totally disrupted the hospitality sector,” says Shawn Basler, Co-CEO and Hospitality Practice leader at Perkins Eastman. It has spawned competition, and has caused hotel chains to reconsider their products and services. To compete with Airbnb and its ilk, hotel chains are emphasizing “authentic experiences” that connect their venues and guests to local lifestyles, arts, and cuisine.

One example is The Hoxton, a 175-key boutique hotel that opened in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, N.Y., last December. Perkins Eastman’s design features “lots of public space that embraces the community,” says Basler, including terraces and courtyards, and a rooftop bar with views across Manhattan. The hotel’s dining area opens to the bar, which opens to the outdoors. “The whole thing becomes activated as a community space,” where locals and guests intermingle, says Basler.

The future will be about bringing people together

No one can say for certain where the shared economy is headed. Peripatetic Millennials, for whom this economy seems tailor made, continue to be somewhat inscrutable when it comes to pinning down their work and lifestyle patterns. And as is the case with almost every big trend, pushback against this tide is inevitable, although it is just as likely that the shared economy will simply flow into the mainstream.

It isn’t clear yet, either, how developers will respond if the shared economy becomes the norm. Some will see it as a threat to the status quo, and panic. But other developers and building owners will ride this wave to new shorelines where customers elect to hang out.

Some developers and their AEC partners are already creating new hangouts where people can share experiences. LandDesign in Charlotte has been working on turning old shopping malls into what Crocker, its President, calls “mini cities,” with restaurants, retail, and high-density office and residential buildings. The offices sometimes include co-working spaces.

These projects, says Crocker, are becoming “mini hubs.” And in a shared economy, that’s not a bad place to be.